Reflections of the Bards Sublime: Lumsk‘s Fremmede Toner (Part 3)

For each of these 6 poems, I’ll provide brief context on the author, as well as the narrative/themes of the text. I’ll then analyze the connections between the songs and their associated poems, and between the mirrored song counterparts. (Reflecting the track list, the Norwegian translations will precede the originals throughout.) Many thanks to our very own Potates in TovH Discord for their help in checking my understanding of the original German lyrics, and providing translations of their own: Hans, EvilHenchman, DarthWTF, and Zocktol. Danke!

Here’re links to Parts I & II!

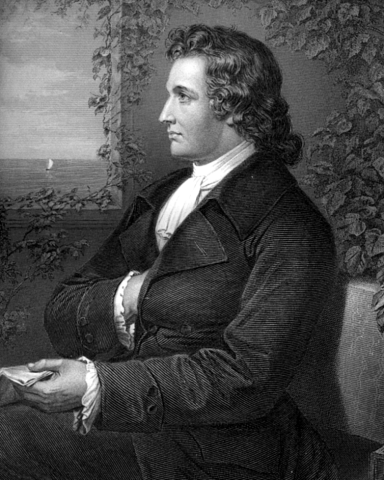

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

“Fiolen” // “Das Veilchen” (c. 1773-4)

(“The Violet”)

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe was a man of many interests; he’s foremost remembered as a playwright, novelist, and poet that made a profound and lasting impact on 19th-century Western thought that continues to the present day. He was a key component of the artistic Sturm und Drang movement, which eschewed the prevailing rationalism of the time in favor of individualism and explorations of extreme emotion. He was also a brilliant scientist whose ideas inspired both Nikola Tesla’s work with alternating currents (AC) and Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution with his studies of the morphology and homology of plants.

His interest in the botanical world bled through into his poetry with “Heideröslein” (1771) and later, the companion poem “Das Veilchen“, which focuses on an anthropomorphized violet. The (male) flower sees a young shepherdess crossing his meadowland home, and longs to catch her eye with his coloration: “bis mich das Liebchen abgepflückt und an dem Busen matt gedrückt” (“for then my love might notice me and on her bosom fasten me”). Unfortunately, her mind is elsewhere: she crushes the violet underfoot, failing to notice him; he happily accepts his death, as it’s brought about solely by her touch, however fleeting.

The stately drumming and shimmering classical guitars that ring in “Fiolen” are sunshine made music—a synesthetic walk through a field in bloom. Klingen’s lilting inflection channels the shepherdess’ “myke trinne og muntert blikk” (“soft steps and cheerful look”) as she makes her way across the meadow, oblivious to the violet vying for her attention. At the close of the second stanza, a discordant pair of piano notes symbolizes footsteps (and the flower’s destruction), leading to an elegy of muffled synth plucks and violin leads. As instrumental layers are stripped away, the violet proclaims “Og dør jeg, dør jeg salig selv” (“And if I die, I die blissfully myself”); Klingen’s isolated voice wilts in the song’s final moments, like petals falling to the ground.

There’s an overall light-hearted feel to “Fiolen” despite the subject matter—an acceptance of the ephemeral; an implicit understanding that the flower is perennial, and will revive in the following year. At just over 2 minutes, it’s the album’s shortest track and we’re not given much time to ruminate on the violet’s fate. “Das Veilchen” is a bleeding heart in comparison; from the solemn bass swells of its first moments, an intense longing descends.

The promise of unrequited love, of deep nostalgia, is channeled through soft piano rock and Klingen’s downcast tone. Bright clusters of keys once more announce the shepherdess’ arrival, but paired with floaty post-rock guitar and emotive leads, the dismal outcome of her journey is all but assured. The instrumental conclusion gives us time to wallow in this deprivation and reminds us that Goethe’s lyrics were never about an actual flower, but rather a young heart crushed by indifference. This more visceral take on the source material hones in on the melodrama to devastating effect.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

“Dagen Er Endt” // “The Day Is Done” (1844)

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was an educator and member of the fireside poets of New England, a group of American poets that first rivaled the fame of the British greats through a combination of accessibility and sentimentality in their works. These poems were the popular entertainment of their time, so named for their intended form of consumption: to be read aloud amongst family and friends by a cozy fire. According to Kevin Stein, “In an era without radio, television, or Internet, these poets were able to garner a general public popularity that has no equivalent in the 21st century” (Stein 8). Longfellow’s influence was heightened by his role as professor at the Bowdoin and Harvard colleges, as well as being the first American to translate Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy in full.

Though he often included stirring historical and mythological themes in his poems, he understood that poetry could just as well serve another purpose: a balm for tired spirits. His “The Day Is Done” centers on such a soul, who at the end of a grueling day longs for an escape from the pressures, the drudgeries of life. They call for a friend to read a “simple and heartfelt lay”—Something with low stakes, devoid of the grandeur of the epics that to their mind “suggest life’s endless toil and endeavor.” With soothing words in the air, their anxiety evaporates, and they’re finally able to let go of the “restless pulse of care”.

We out here at the Longfellow Memorial in Cambridge, MA.

The dreary synth pad that introduces “Dagen Er Endt” shrouds the narrator’s vision in fog: “Landsbyens lys så jeg blinke / i tåke og regn” (“I saw the lights of the village twinkling / in fog and rain”). Their downtrodden mood eventually brightens as they meet up with a friend for an evening visit. Their conversation first takes the form of harmonized Thin Lizzy leads and rotary organ, and eventually, a duet between Klingen and Laugtug’s violin, in which vocal cords and strings intertwine and seem to speak in one voice.

As the song continues to its midpoint, the emotional impact reaches its peak with an enchanting ballad; the narrator asks their friend to choose a beloved poem “og lån til poetens strofer / den skjønnhet som bor i din røst” (“and lend to the poet’s stanzas / the beauty that lives in your voice”). An extended coda follows with dense layers of overdriven church organ and bluesy solos that call to mind Pallbearer run through a classic rock filter. A scintillating piano line brings the track to a close, offering us the catharsis “av livets vidundermusikk” (“of the wonderful music of life”).

Much like “Dagen Er Endt”, the final track “The Day Is Done” unfolds as a series of ballads interwoven with rock and metal elements. Samuelsen returns on vocals once more, imparting the first stanzas with the narrator’s exhaustion. The album’s pristine production allows listeners to hear the malleability of his voice; he shifts effortlessly from crooning to a mid-range rasp as doom metal chords begin to thunder. As he invokes “the grand old masters…Whose distant footsteps echo / Through the corridors of Time”, a vaguely “Baba O’Riley“an keyboard rings out. It’s a strange mix of ideas: the majestic march of the riffs brings to mind ancient ruins and the epics of Homer and Milton, while the prog rock flourishes recall our modern world. This section effectively distills the essence of the record—The marriage of disparate art forms and eras.

The desk in Longfellow’s home where he wrote The Day Is Done. Note the little Goethe figure that would’ve stared at him in constant judgment.

When Klingen joins in, cheerfully singing “Read from some humbler poet / whose songs gushed from his heart”, my initial reaction was to recoil—after all, I am a big, tough metal fan and the sentimentality here was nearly too saccharine for my big, tough self. After a few listens, however, this stanza broke through. It peeled back layers of bitterness and defense that have accrued over years of increasing agitation and burnout. I accepted the ethos of fireside poetry, allowing myself a moment of comfort. I allowed myself to be cradled by lovely soundwaves.

The remaining minutes of Fremmede Toner are a celebration; a victory over constant worry; proof that one can still hear melodies through the dissonance of our modern age. Echoes of Pink Floyd ripple out during a jam session replete with languid Gilmour-style leads, and the album closes with a triumphant shout from Samuelsen as the volume swells to its apex. And with that, the day is done.