Remembering Roland Emmerich’s Godzilla, 20 Years Later

May 20th, 1998. A young Dubs had just finished eating a meal at Taco Bell with his dad and two of his boyhood friends; a commemorative Godzilla car-window cup holder was securely in his grasp. A gentle sun burned with infinite possibility in the beautiful, early spring Colorado sky. It was a perfect day, one that young Dubs had been anticipating for months. For today was the day that he would finally get to see the first* American Godzilla film in theaters. And as the opening credits rolled over those scenes of nuclear devastation and Mother Nature persisting in the face of man’s machinations, young Dubs knew nothing but pure, unfiltered joy. Oh, how time makes fools of us all.

Little did I know then how truly disappointing to the vast majority of kaiju fans was Roland Emmerich’s bastardization of the King of the Monsters. I was 9 years old and still riding high on the dinosaur craze of the 1990s. Plus, I loved every single Godzilla film I had watched since my dad first brought home Godzilla, King of the Monsters when I was only five. I had almost every line to Godzilla’s Revenge (a movie so terrible it’s practically incredible) memorized, for goodness sake! Of course I was going to love TriStar’s take on the Japanese Giant.

People who complain about Godzilla ’98 have probably never seen Godzilla’s Revenge.

Today, just a couple of measly sunrises removed from TriStar’s Godzilla’s 20th anniversary, it’s much harder to overlook the flaws that eluded my 9-year-old brain. The acting is abysmal; try as he might, Ferris Buell… er Matthew Broderick does not a compelling sci-fi/action hero make (a fact even he acknowledged later in his career). But Broderick alone couldn’t shoulder all the miscasting blame even if he wanted to; co-star Maria Pitillo won a Razzie for her uninspired performance as love interest Audrey Timmonds, and the other characters were so laughably underdeveloped that audiences felt zero attachment to their suddenly threatened metropolitan lives. Even the uber-cool Jean Reno could work little magic with the poorly conceived French Roast one-liners his classy spy character Philippe Roaché delivered.

It would be unfair to have expected the cast to squeeze much blood from the polished turd of a stone delivered to them by Emmerich and co-conspirator Dean Devlin, however. Initial storyboards were scrapped, a slipshod script was drafted, and filming was rushed over a flighty 13-days in New York City (with a handful of other locales also shot over a brief period). The production team crunched to meet an accelerated deadline of Memorial Day weekend, less than a year after the initial shots in NYC. Perhaps most tellingly, test screenings were denied.

Seriously, Jean Reno was wasted on this movie.

That stilted writing process is at least partially responsible for the hack-job of a script that sees Broderick’s “Worm Guy” Nick Tatopoulos talking about fish and how Timmonds broke his heart in college over and over. It’s also responsible for a number of jokes that have aged poorly (at one point Arabella Fields as Lucy Palotti screams at Hank Azaria as cameraman Animal, “Get back here, you retahd!”) and a nonsensical plot that has a bumbling army colonel (Kevin Dunn), a blustering Roger Ebert-parody mayor (Michael Lerner), and a bafflingly menacing French Secret Service team attempting to destroy a wild animal that barely kills anyone for the film’s entire duration. The larger issue, however, is the contempt in which Emmerich and Devlin held the property they’d been handed on a silver platter.

“Both of us thought it was a dopey idea the first time we talked. When Chris came back to us, we still thought it was a dopey idea.” – Dean Devlin

“[Regarding the original script] The last half was like watching two creatures go at it. I simply don’t like that.” – Roland Emmerich

As Rob Fried, who had originally worked with film mogul Henry G. Saperstein (who himself had appealed to Toho for years to allow American studios to produce an original Godzilla film rather than the dubs and localizations of Toho properties he had personally been responsible for) to secure the rights and release Godzilla to an American audience, put it, “The Sony executive team that took over Godzilla was one of the worst cases of executive incompetence I have observed in my twenty year career. One of the golden assets of our time, which was hand-delivered to them, was managed as poorly and ineptly as anybody can manage an asset. They took a jewel and turned it into dust.”

The King of the Monsters, brought low by hunger.

Stan Winston’s Godzilla

That wasn’t always the plan, though. Saperstein and Fried originally tapped Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio to draft a script, one that director Jan De Bont (Speed, Twister) would craft into a fascinating new tale of an Atlantean Godzilla battling a shapeshifting alien beast called the Gryphon. De Bont’s film was to be the first in a trilogy that featured a more saurian, upright Godzilla designed by Stan Winston, shown to the right. De Bont’s film, as detailed in this fascinating blog article you should definitely take the time to read, was a genuinely interesting pitch and seemed to win over Godzilla’s creative parents. Koichi Kawakita, the special effects director for a number of Toho’s kaiju eiga, famously opined, “I have great expectations. I’m looking forward to seeing it, not only because I direct special effects for Godzilla films but also because I am a movie fan.” Sadly, De Bont’s vision would never come to pass. TriStar and Sony, glutted on the cash inflow of Independence Day and leery of a campy giant monster brawl, forced De Bont off the project when they refused his smaller budget of $100 million.

One rendering of Stan Winston’s Gryphon

The film we did get, one that featured an irradiated iguana as the titular monster, was a far cry from Godzilla’s Japanese origins. Throughout the film, Godzilla flees from the military, lays eggs in a sequence eerily reminiscent of the Jurassic Park films, and generally spends more time digging holes than smashing buildings. Emmerich and Devlin intentionally deprived Godzilla of any form of characterization beyond that of a frightened animal, and it was this key flaw that film goers universally despised. This Godzilla had no purpose but survival and no enemy but an incompetent and boring human cast. Adding insult to injury, Godzilla, King of the Monsters, was felled by a handful of missiles after being ensnared in bridge cables.

It’s no wonder Godzilla fans widely derided this version of the monster as “G.I.N.O.” (Godzilla In Name Only).

And yet…

Despite all its flaws, from its nonsensical script to its limp scripting to its hobbling of an international cinematic icon, Godzilla ’98, as a monster film rather than a GODZILLA film, isn’t really all that bad. Sure, most of the aforementioned flaws would still remain even if the monster had been called by any other name, but at least the climax on the bridge would not have felt so anticlimactic. The hide-n-seek action also wouldn’t have been nearly as tedious if we hadn’t been anticipating massive destruction throughout the entire run time. Even the lack of Godzilla’s signature atomic breath (replaced in film by either a gaseous belch or a flame burst, depending on your interpretation of a couple of vague scenes) would not have been so odious if the monster were indeed a mutant aberration.

Plus, the monster design, stripped of the Godzilla name, is fantastic. Those dual-ridged dorsal plates are terrific, and the longer limbs and horizontal pose lend the beast a sense of speed and agility rather than brute force. And although the CGI may look a bit rough compared to modern films like The Last Jedi or The Avengers, the effects were cutting edge for the time, smartly making use of waist-down shots and puppetry where possible to lend the fleet monster’s movements an elusive and taut edge. Critics may have panned everything else about the film, but the special effects were widely considered sophisticated and awe-inspiring.

Ultimately, part of whatever 9-year-old Dubs saw in the film remains with me today. Although this is one of the harder Godzilla films to sit through, it’s certainly better than Godzilla’s Revenge or the majority of the Showa Gamera films, not to mention other American productions like Cloverfield (great idea; obnoxious execution) or Monsters: Dark Continent. It lacks the requisite destruction and cast to pull off the gravitas of which some of the best films in the genre are capable, nor does it have the irreverent absurdity necessary to make its sloppy writing endearing in the way movies like Rampage or Kong: Skull Island are. What we have is a poorly written film with a terrific-looking beasty that bears an unfortunate moniker it can never live up to. In the grand canon of kaiju cinema, it’s near the top of the lowest tier, and on the rare night when you just want to drink beer and turn your brain off but don’t want to sink to the level of Yonggary, G.I.N.O. will suffice.

Fortunately, the monster in Godzilla ’98 would find redemption years later. Godzilla itself turned a decent profit, and although TriStar canceled Emmerich’s and Devlin’s treatment for a sequel, the monster himself starred in the delightful animated series that followed. Godzilla: The Series, which ran for two seasons on Fox Kids, restored the monster’s atomic breath and supernatural endurance; even better, it pitted Godzilla Jr. (as the show’s version of the Worm Guy christened him) against some truly fantastic monsters. Seriously, Godzilla: The Series feature some of the coolest and most imaginative monster ideas you’ll find outside of Japanese takusatsu shows, and even grudging fans who hated G.I.N.O. praised Crustaceous Rex and the undeniable rogues gallery of Godzilla Jr.

Toho would eventually go on to welcome their orphaned son back into the monster family, first mentioning the American monster in 2002’s Godzilla Against Mechagodzilla and then pitting him against the King of the Monsters in 2004’s Godzilla: Final Wars. The newly re-branded Zilla may not have lasted long, but at least he now had his own identity, set free from the burdensome shackles that had dragged him down since 1998.

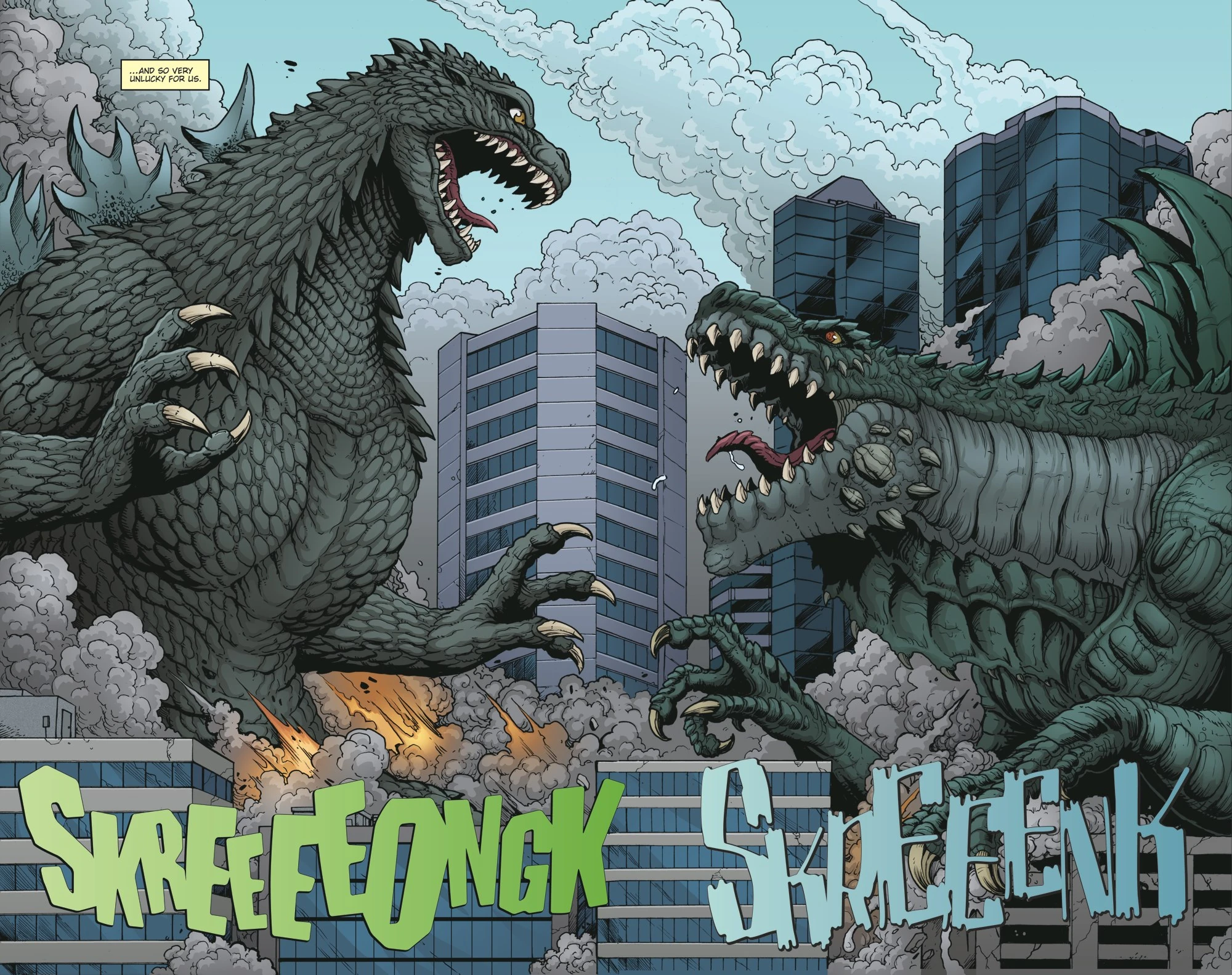

Zilla has continued to appear in various Godzilla media properties, including a great turn as a mysterious contender drawn wonderfully by Matt Frank in Godzilla: Rulers of Earth. In that comic, Zilla holds his own against the King of the Monsters, even joining Godzilla and the other kaiju in the final pitch against the Trilopods. It’s nice to see that the reptilian beast wasn’t discarded after his film’s critical flop.

Art by Matt Frank

Of course, no discussion of Godzilla would be complete without a mention of the smash hit soundtrack. Godzilla: The Album, released through Epic Records, debuted at No. 2 on the Billboard 200 and was certified Platinum by the RIAA. Like many of the mega soundtracks released and consumed en masse in the 1990s, Godzilla: The Album mostly consisted of alt-rock hits. Tracks from Rage Against the Machine, Foo Fighters, Silverchair, and The Wallflowers were well regarded (with the latter peaking at number 10 on the Billboard Modern Rock Tracks), but the biggest song on the record is undeniably the heavily promoted collaboration “Come With Me,” penned by Puff Daddy and Led Zepplin guitarist/rock spider Jimmy Page. “Come With Me” features a tough-as-nails backbeat from Led Zepp’s “Kashmir” with the drums and riff cranked to 11. Sean Combs’ nonsensical rapping may feel contrived and soulless today, but this song was EVERYWHERE in 1998. Even a young Dubs, who generally only listened to whatever country radio station his parents had on at the time, was aware of it; dare I say this song may even have sparked an interest in the harder edges of music for a pre-pubescent W.? And look, I’m just gonna get a hot take out of the way before concluding this article: The “Kashmir” riff sounds even better and harder (although definitely less grandiose) in “Come With Me.” Be it known.

Thankfully, the U.S. got a second chance at Godzilla, and although dyed in the wool fans were a bit split on Legendary’s Godzilla (2014), the film (and its monster!) were generally much more warmly received by wider audiences. The new American Godzilla will return next year in Godzilla: King of the Monsters and then do final battle against the terrific new adaption of King Kong in Godzilla vs. Kong the following year.

As for Zilla, well, both my inner child and I are hoping we see the black sheep on the silver screen again soon!

*first: Note that various Godzilla films had been adapted for American audiences, in some cases even featuring new scenes and dialogue (see Godzilla, King of the Monsters), but 1998’s Godzilla was truly the first wholly original American take on the monster.